Where

This morning, the sun is high. It lights up the occasional sprays of spindrift in silver-white sparks. From this height, the ocean looks endless like the sky. Blue and quiet.

But the storms are coming…

The Outer Hebrides are a chain of islands approximately forty miles off the west coast of mainland Scotland. Of the sixty-five islands, only fifteen are inhabited. North to south, the main islands are Lewis & Harris, North Uist, Benbecula, South Uist, and Barra – one hundred and thirty miles of sandy beaches, machair meadows, and treeless peat moors; lochs and lochans, mountains, and moonrock. Scottish Gaelic is the predominant language of the 27,000 people who live there. The island relies heavily on sea transport for travel and the climate is stormy but mild; many boats and ships have been wrecked over the years – the coastlines are studded with stony memorials.

I can see the storms coming in the spray blown from the crests of waves and in the scattered whitecaps out towards the horizon. In the slow steady leaching of light from the sky, a little earlier each day. And I can feel them in the air and against my skin. A prickle. A shiver of old fear.

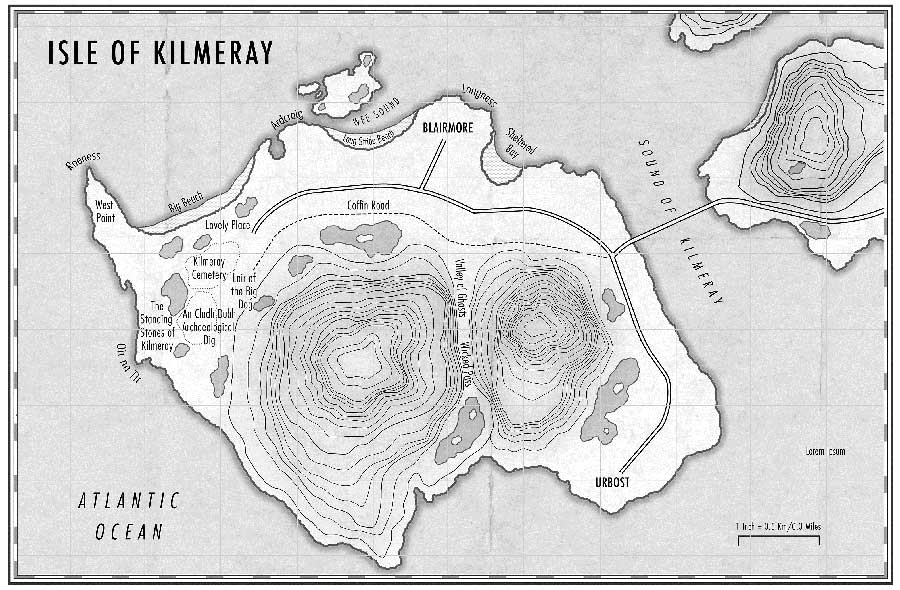

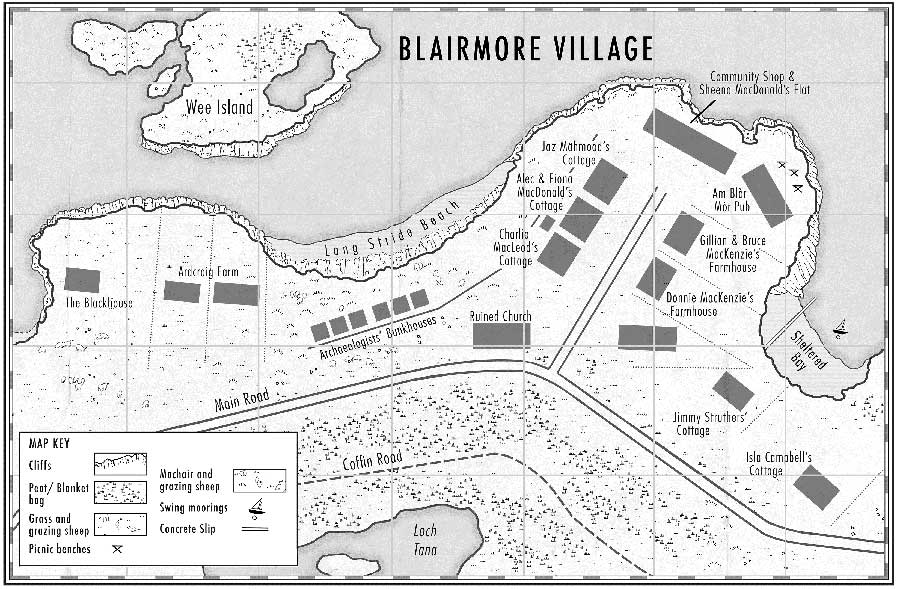

the isle of kilmeray

The Isle of Kilmeray (Eilean Cill Maraigh) in The Blackhouse, is based on the uninhabited island of Scarp off the west coast of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. Creating Kilmeray’s villages, mountains and lochs, peat bogs, machair, moors, beaches, and standing stones was a wonderful experience – not to mention inventing eerie place names in Scots Gaelic:

–Gleann nam Bòcan (Valley of Ghosts)

–An Droch Chadha (Wicked Pass)

–Glumag a’ Bhròin (The Pool of Sorrow)

–Sid a’ Choin Mhòir (Lair of the Big Dog)

But seeing the island brought to life in the brilliant maps that HarperCollins’ terrific art dept. produced for the book was even better (and far, far better than the maps I sent them!)

The night is dry, but the wind has picked up. I can hear it whistling through narrow spaces, howling around the cliffs and Ben Wyvis, and I imagine this little island shrinking slowly, smaller and smaller, scoured and consumed by the Atlantic winds and waves.

ARDSHADER

Ardshader (Àrd Shiadair), the fishing village on Lewis where Robert grew up is also fictional. But there are many places in The Blackhouse that do exist, and all are very close to my heart: Tarbert, Timsgarry, Miavaig, Breanish, and Valtos, to name only a few.

STORNOWAY

The capital of the Isle of Lewis & Harris, it’s always a hive of activity: a busy fishing harbour and ferry port, narrow streets lined with brightly-coloured hotels and pubs and restaurants, and the vast and beautiful woodland ‘Grounds’ across the water at Lews Castle. Stornoway also has the island’s only two supermarkets. When I was living on Lewis, I used to look forward to our monthly cross-island trip to restock. After the remote wildness of the west coast, Stornoway always felt like a metropolis!

UIG SANDS

Ardshader, where Robert grew up, is based very loosely on the area around Uig Sands and Ardroil to the northeast of Scarp. Uig is a beautiful area on the rugged west coast of Lewis, and Uig Sands itself is vast and remote and wild. In 1831, 78 Viking chess pieces dating back to the 12th century were found on the beach. In fact, the name Uig is itself derived from the Norse word for ‘bay’.

Because it’s a place that I love, that I know very well and have been visiting for years, I decided to make Uig Sands (Ardshader) the setting for one of the most important and powerful events in The Blackhouse.

CLIFF

Cliff is a small settlement on the Valtos peninsula on the west coast of Lewis, south of Uig. I was lucky enough to live there for several months in 2017, in a wonderful house above Cliff Beach. It was in that house that I finished writing my first draft of Mirrorland. It was also while living in Cliff that I initially had the idea for The Blackhouse. Shortly after we arrived, a man’s body was washed up on Cliff Beach; he’d drowned farther down the coast. There have only been two murders in the Western Isles in fifty years, but it brought home to us the very real, albeit different, dangers of living in the remote part of an already isolated island. And when the tourists left and the winter storms arrived, that isolation only began to feel more acute…

But what really struck me when I lived in Cliff was that although I’d been visiting Lewis & Harris for years, this was the first time I’d felt like I was actually living there, that I was part of these wonderful close-knit communities – and it was a completely different experience from being a tourist. One that took many months to get used to.

THE BLACKHOUSE

A Blackhouse is a traditional type of house which used to be common in Ireland, the Scottish Highlands, and the Outer Hebrides.

The buildings were generally built with dry-stone walls packed with earth, at least two feet thick with very small windows to keep out the Atlantic storms. The floor was flagstones or packed earth with a central hearth for the fire. The roof was thatched with turf or straw, and there was no chimney for the smoke to escape through – instead, the smoke made its way through the roof. This led to the soot blackening of the interior which may explain the origins of the name blackhouse. They often accommodated livestock; people lived at one end and the animals lived at the other with a partition between them.

Blackhouses were eventually replaced with white houses, which are white-washed one-and-a-half storey houses with the dormer bedrooms in the roof space. In places like Lewis & Harris, it’s not unusual to see the ruins of a blackhouse alongside a newer white house.

The titular Blackhouse is very much based on a real place on Harris that I know very well. It’s a replica of a traditional blackhouse. Although I conceived The Blackhouse’s story while living in Cliff, the blackhouse itself was most definitely inspired by this house in Harris. Both the outside appearance and inside layout of the blackhouse is almost identical – with a few necessarily creepy tweaks! Partly because it’s always far easier to write about what you know, but also because as a place it had exactly the right vibe I was looking for – cosy if basic, and deceptively comforting – very Hebridean in other words!

THE COFFIN ROAD

There are many coffin roads in the Outer Hebrides, where islanders traditionally carried the coffins of loved ones from the rocky east to the machair graveyards of the west coast. I’ve walked the Coffin Road that crosses Harris from the Bays of Harris in the east to Luskentyre Beach in the west. Crossing through terrain that has never been inhabited (almost all townships are located on the coastal roads), and imagining centuries of people carrying coffins to their final resting places is an eerie yet peaceful experience. At intervals, there are stone cairns which are said to have acted as rest stops for the coffins en route.

But, strangely, the worst thing is neither the claustrophobic dark nor the sense that I might never reach the end of it. It’s the almost silent silence. I’m too used now to wind, to waves, to wild. This dark, close pass punctuated by nothing other than falling scree—not even birdsong—is more than unnerving. It makes me flinch every time I hear anything at all.

STANDING STONES

Standing stones, stone circles, and monoliths are everywhere on the Isle of Lewis & Harris. It’s not unusual to drive past them, or see them in fields with sheep or Highland cows. It’s a strange experience – I never quite got used to seeing them everywhere. I’m more familiar with places like Stonehenge: a car park and a visitor centre with overpriced merchandise, and a wide cordon that ensures you can only look and never touch.

Even the most important stones at Callanish on Lewis are very accessible. They are huge standing stones on top of a hill, formed not in a circle but a cross. At the centre of the cross is a huge monolith and a chambered cairn. They’re said to be one of the most important and significant megalithic complexes in Europe, older than Stonehenge. And they do have a visitor centre. But it’s an open site – you can always visit, no matter the time of year. There are no cordons. And there are two other Callanish standing circles nearby in fields with only the cows for company.

I think, weirdly, that it’s this accessibility that makes them feel so special. You can walk among them, touch them. And they absolutely contribute to the wonderful other-worldly atmosphere that the islands have. In Celtic lore, the Western Isles are said to be thin places, spiritual landscapes where the veil between this world and other worlds are at their thinnest. I used this idea in The Blackhouse a lot; in fact, the story’s original title was A Thin Place!

There’s a peace here. A kind of quiet that even a storm can’t disturb or destroy. Like those flat, impassive stones standing sentinel on the cliffs at Oir na Tìr. So tall they can block out the sun.

LIGHTHOUSE

There are about half a dozen Stevenson lighthouses on the coast of Lewis & Harris, and over 200 around Scotland. They were designed and built by multiple generations of the Stevenson family. Robert Louis Stevenson famously became a writer rather than an engineer, but it’s rumoured that Fidra Island and its lighthouse on the east coast of Scotland inspired ‘Treasure Island’.

All the Stevenson lighthouses are very distinctive: huge structures, either red-and-white striped, or more commonly cream-white with ochre trim. And they’re very much something that I associate with Lewis & Harris: they’re quite an eerie sight at night; yet another reminder of the dangers of the Atlantic, and, of course, of fishing in the Atlantic – which is a core part of The Blackhouse story. Although the lighthouse at Ardshader is fictional, it’s based on the Tiumpan Head Lighthouse on Point near Stornoway.

TIDE BELL

There’s a tide bell in The Blackhouse that sits in Ardshader Bay and starts to ring as the tide rises. There is just such a tidal bell at Bostadh on the small island of Great Bernera off the west coast of Lewis. It was created by the sculptor, Marcus Vergette, who installed eight of these bells around the UK, to highlight climate change in terms of rising sea levels.

I was determined to use a similar tide bell in The Blackhouse because it’s the most affecting and eerie experience to listen to the bell get louder and louder as the seas grow bigger and higher, until it is drowned back into silence by the waves.

They were always what he remembered the most. Sometimes they were all he could think about.

The tide bell. And the black tower.

FINALLY

Last but not least, these handsome fellows just had to appear somewhere in The Blackhouse! For months, Shug and Hamish, as they came to be known, were stationed beside the road out of Miavaig, and although we had no idea what they were for, we became very attached to them!

(Shug unfortunately lost both his arms and his bagpipes at some point.)